This past July, I flew to Chicago to attend Justice Day 2015, the

fiftieth anniversary of the North Shore Summer Project, a 1965 fair housing

effort to challenge the practices that perpetuated housing segregation,

practices that had been taken for granted for so many years. It led me to look

back even further in time.

In the mid-1940s, at the Charles C. Lea elementary school in the

Philadelphia neighborhood now known as University City, there were a few

“colored” children (“African-American” wouldn’t come into use for some forty

years), and I never wondered why none of them lived on my street. A few years

later at the Philadelphia High School for Girls I became friendly with a few

“Negro” girls, but none of them lived in my neighborhood, and aside from a

couple of evenings when my mother invited some of them to dinner at our

apartment, I didn’t see any of them outside of school. At Penn in the 1950s I can’t

remember any students of color. No wonder: our 1955 yearbook shows only one

black woman in our entire graduating class. It’s a snapshot of the times.

I never considered myself prejudiced, but I’m mortified to admit I

was blind to the barriers that separated people by skin color. It wasn’t until

the rise of the civil rights movement in the 1960s that my consciousness was

raised. I was horrified by the violence down South. But as a Manhattan mother of

three children under six, I didn't feel I could go to Mississippi to fight for

justice. When I heard about the New York-based National Committee against

Discrimination in Housing, I realized that I could work for change in my own

backyard. I joined the staff of the NCDH.

New York City had a fair housing law – but if people didn't apply

for housing, the law meant nothing. I wrote "Neighborhood Profiles,"

describing areas of the five boroughs where few minorities lived – and which

many nonwhite home seekers knew little or nothing about. We distributed these

profiles and followed up with home-seeking families. Whenever minority

applicant were refused, my anger helped me get through the process of lying to

make my profile sound like theirs and to overcome my nervousness about

testifying in court. I became more and more incensed that people should be

treated this way.

Late in 1964, my family

moved from Manhattan to Glencoe, a northern lakeside suburb of Chicago, and I met

Philadelphian Bill Moyer, who was working with the American Friends Service

Committee. Bill, a mild-mannered social worker, was a genius at organizing. “There’s

just as much racism in Chicago as there is in Mississippi,” he told me. “But

white people – even liberals – don’t realize it. We want to make them see it.”

His idea was to launch an Open Housing movement in the thirteen almost-all-white

suburbs along the shores of Lake Michigan by emulating the Freedom Marches in

the south. He named this1965 effort the North Shore Summer Project, after the

Mississippi Summer Project.

“Down South,” Bill told me in his soft-spoken way, “the movement

is focused on voting rights. But these North Shore suburbs don't have to deny black

people the right to vote – they just deny them the right to live here. Only two

of these suburbs – Evanston and Glencoe – have real black populations. They

also have real ghettoes to keep them in.”

The

Quakers, Bill explained, wanted to expand white people’s knowledge of racism: “Black

people don't have to learn about prejudice: they’re living it.” Bill’s sense of mission was contagious, and I

enthusiastically agreed to serve as volunteer public relations director.

It was a heady time. I was working with

representatives from the worlds of religion, civic involvement, and social

activism. Because these suburbs were almost totally white, we had black

committee members from only two towns, the Reverend Emory Davis from Evanston

and Gerry Washington, a Glencoe mother whose daughters went to school with and

played with mine. We met with realtors, conducted vigils outside their offices,

and distributed literature about their discriminatory practices. We marched and

we sang. We recruited college students to interview North Shore residents, who declared

overwhelmingly that they would welcome nonwhite neighbors, despite the

realtors’ contention that they were following homeowners’ wishes by refusing to

show houses to nonwhite home-seekers. Our major coup was bringing the Rev.

Martin Luther King Jr. to Winnetka, the whitest of these suburbs, to speak to a

crowd of 10,000 on the Village Green.

I issued weekly news releases, was quoted in the local press – and

received hate mail. Instead of intimidating me, it let me know that our efforts

were being noticed and inspired me to become even more committed. (Of course

hate mail in Glencoe was not as scary as hate mail in Biloxi.) Our final event

was the August 29 six-mile march from our NSSP Freedom Center in Winnetka to

the Evanston-North Shore Board of Realtors, where we presented a summary of the

project’s findings at a rally, followed by an all-night vigil. Then the NSSP,

which from its conception had been time-limited, disbanded. Our students went

back to school, our AFSC sponsorship ended, and most of the volunteers moved on

to other forms of activism.

Soon afterwards my family moved away from Glencoe, and I lost

touch with my fellow volunteers. Last spring I reconnected with Carol Kleiman,

another former Philadelphian. Carol told me that when she had told Dr. King she

wanted to move from Glenview to an integrated area, he told her, “No, stay

where you are. Lance the boil.” The “boil” was segregation, and a few results

of that “lancing” can be seen in activities we set in motion.

Although the NSSP failed with Harriette and McLouis Robinet (a

physicist then teaching at the University of Illinois), who were not able to

buy a house on the North Shore and suffered humiliation while looking, they

were energized to continue their search and did buy in the previously all white

western suburb of Oak Park, where the family still lives. Harriette wrote about

her family’s experience for Redbook,

launching an award-winning career writing multicultural historical fiction for

children.

David and Mary James’s North Shore story is more successful. The

first African American to buy in Winnetka, David, a lawyer and former Tuskegee

airman, founded a program for suburban and inner-city children, now a day camp

for 7- to 12-year-olds. It was – and still is – infuriating to learn how hard

it was for so many good people to do a simple thing like housing their

families.

Fortified by the 1968 national Fair Housing Act and moving beyond

educating the white community, Winnetka’s Open Communities now works to

influence housing policy and enforce the law. At the anniversary celebration it

sponsored, the crowd of about 1,000 –

many of whom had not been born in 1965 – gathered on the Village Green where

Dr. King had addressed the largest crowd ever to assemble there and pledged to

continue the work. The bronze marker

memorializing him, installed with money raised by Winnetka schoolchildren,

gleamed in the sunlight, heralding a brighter future.

But

the wheels of justice still grind exceedingly slow. Even though in 1968 the national

Fair Housing Act became law, many brokers have simply gone underground. The

North Shore suburbs are still almost entirely white. It’s disappointing, half a century later, that there’s

still a need for a follow-up to the push to open closed borders. I briefly wondered

whether our efforts had had any impact at all. But then I reminded myself that

change had occurred. That even when an ideal is not fully realized, our efforts

were not in vain. Although the numbers of nonwhite residents in these suburbs

are still small, they’re larger than they had been.

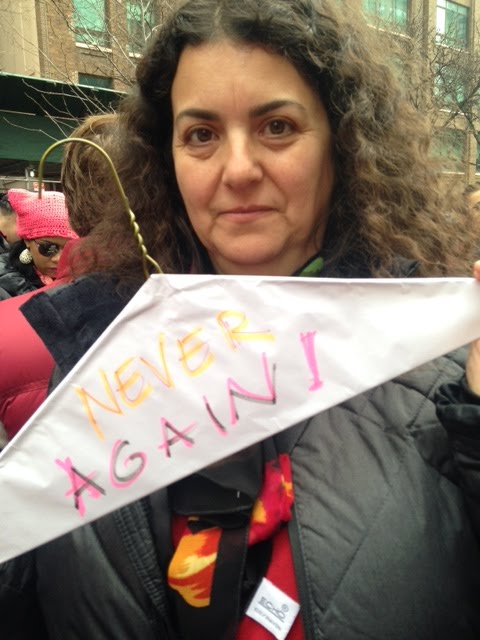

The biggest change was in us

mostly white volunteers, who learned from our educators, the black volunteers

and home-seekers. Working in the context of the society of fifty years ago, we

morphed from white liberals to white activists as we realized that a new world

will be formed in new ways. Many of us went on to work for change in many

facets of society, including but not limited to racial equality. So yes, we can

wear the sobriquet of “do-gooder” proudly. We did do some good – largely for

ourselves, but also for thirteen communities. We will never go back to who we

were before – just as the North Shore is no longer what it was. I remember the

words of Mahatma Gandhi: “Whatever you do will be insignificant, but it is very

important that you do it.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)